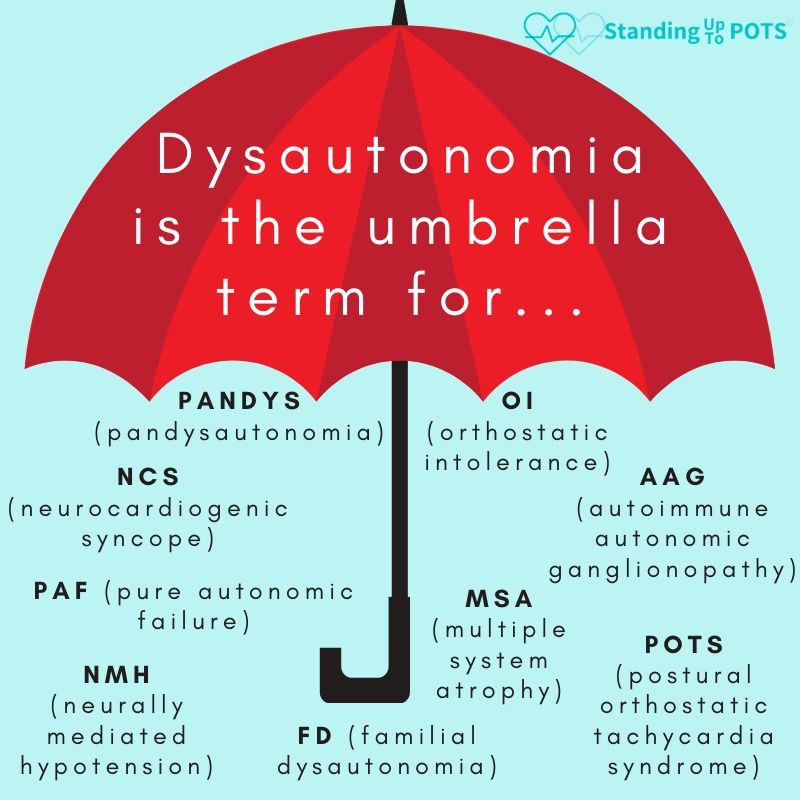

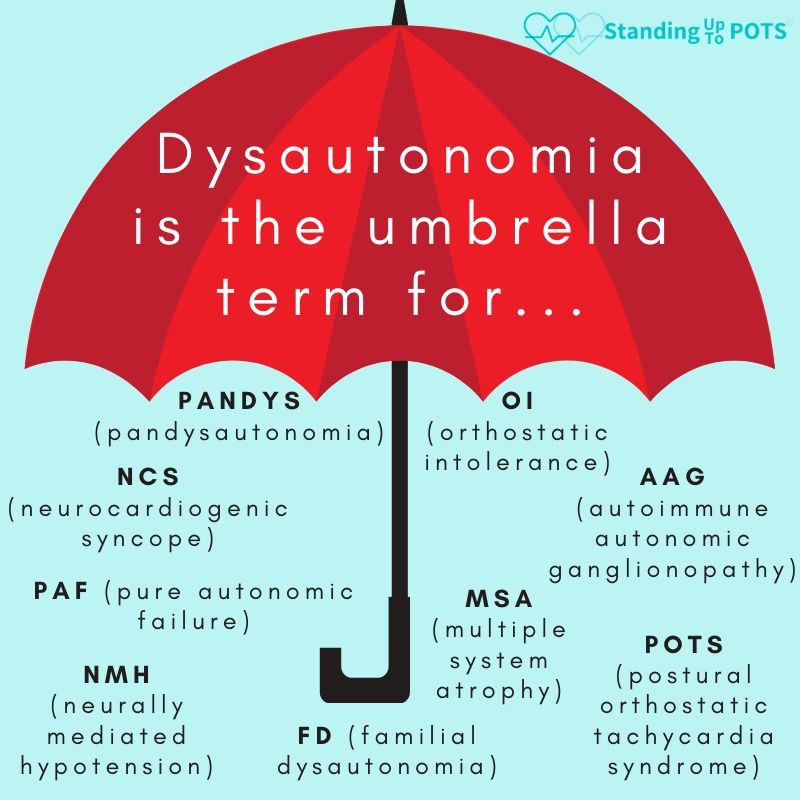

POTS, a common form of dysautonomia, is an invisible illness that largely affects women between the ages of 15 and 50 and is estimated to affect 1% of teenagers and a total of 1-3 million people in the United States. POTS can be triggered by pregnancy, major surgery, trauma, or a viral infection like mononucleosis or Lyme disease. Finally, 25% of POTS patients are so debilitated by illness that they cannot work or attend school.

POTS Symptoms: Because the autonomic nervous system is disrupted, a wide variety of symptoms may be present that span multiple organ systems.

|

|

Common Comorbidities: The most common comorbidities include chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and fibromyalgia. Others include:

|

|

Diagnosing POTS

When a practitioner has a young patient (ages 15-50) with widespread, non-specific symptoms, POTS should be considered. 80% of POTS patients have been misdiagnosed and are told that their symptoms are “all in their head” before they are correctly diagnosed. As a result, patients may be frustrated by the time they reach your office. Thanks for taking the time to learn about POTS.

| Recommendations - Investigation of POTS from Sheldon et al. 2015. Heart Rhythm 12(6): e44 | Class | Level |

|---|---|---|

| A complete history and physical exam with orthostatic vital signs and 12-lead EKG should be performed on patients being assessed for POTS | I | E |

| Complete blood count and thyroid function studies can be useful for selected patients being assessed for POTS | IIa | E |

| A 24-hour Holter monitor may be considered for selected patients being assessed for POTS, although its clinical efficacy is uncertain | IIb | E |

| Detailed autonomic testing, transthoracic echocardiogram, tilt-table testing, and exercise stress testing may be considered for selected patients | IIb | E |

The best way to diagnose POTS currently is with a Standing Test. Take pulse and blood pressure in supine position after 5 minutes. Have patient stand without leaning for 2-10 minutes and repeat pulse and blood pressure every 2 minutes.

- Adults: heart rate ≥ 30 bpm upon standing may indicate POTS

- Children: heart rate ≥ 40 bpm upon standing may indicate POTS

- Blood pressure should not decrease by more than 20/10 mmHg upon standing.

You may also choose to refer your patient to an autonomic specialist to have a tilt table test and quantitative sudomotor autonomic reflex testing (QSART).

Treating POTS Symptoms

| Recommendations - Treatment for POTS taken from Sheldon et al. 2015. Heart Rhythm 12(6): e44 | Class | Level |

|---|---|---|

| A regular, structured, and progressive exercise program for patients with POTS can be effective | IIa | B-R |

| It is reasonable to treat patients with POTS who have short-term clinical decompensations with an acute intravenous infusion of up to 2 L of saline | IIa | C |

| Patients with POTS might be best managed with a multidisciplinary approach | IIb | E |

| The consumption of up to 2-3 L of water and 10-12g of NaCl daily by patients with POTS may be considered | IIb | E |

| It seems reasonable to treat patients with POTS with fludrocortisone or pyridostigmine | IIb | C |

| Treatment of patients with POTS with midodrine or low-dose propranolol may be considered | IIb | B-R |

| It seems reasonable to treat patients with POTS who have prominent hyperadrenergic features with clonidine or alpha-methyldopa | IIb | E |

| Drugs that block the norepinephrine reuptake transporter can worsen symptoms in patients with POTS and should not be administered | III | B-R |

| Regular intravenous infusions of saline in patients with POTS are not recommended in the absence of evidence, and chronic or repeated intravenous cannulation is potentially harmful | III | E |

| Radiofrequency sinus node modification, surgical correction of Chiari malformation type I, and balloon dilation or stenting of the jugular vein are not recommended for routine use in patients with POTS and are potentially harmful | III | B-NR |

For a modified POTS exercise program from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia that includes the basics of strength training and cardiovascular training.

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis varies based on the underlying cause and overall severity of symptoms. A study of 121 pediatric POTS patients over time found cumulative symptom-free rate gradually increased over time, especially if the illness was diagnosed early and proper treatment was initiated quickly (Tao et al. 2019). However, POTS does not simply disappear, and most teens don’t outgrow this disorder. In fact, only 20% of teens made a full recovery within 10 years. Only 50% of people who develop POTS after a viral infection recover in five years, while those with primary hyperadrenergic form will require lifelong treatment (Agarwal et al. 2007).

A study of 42 adult POTS patients found significant improvement in symptom burden and quality of life after 2 years of treatment, but the symptom burden was still high and did not improve occupational status (Dipaola et al. 2020).

In a mailed follow-up study of POTS patients, with only a 34% response rate (may be skewed toward positive outcomes), the prognosis for pediatric POTS cases was found to be:

- 33% of pediatric patients had complete resolution of symptoms after 5 years

- 51% reported persistent but improved symptoms

- 16% reported intermittent symptoms

- 71% considered their health to be at least “good.” (Bhatia et al. 2016)

For individuals with POTS secondary to another illness, treatment of the underlying disorder (Addison’s disease, Crohn’s disease, mast cell activation syndrome, etc.) is critical in order to control POTS symptoms. Compassionate continuing care is critical to achieve a decent quality of life for these chronically ill patients.